- (i) by recognising that employment relationships must be built on good faith behaviour; and

- (ii) by acknowledging and addressing the inherent inequality of bargaining power in employment relationships; and

- (iii) by promoting collective bargaining; and

- (iv) by protecting the integrity of individual choice; and

- (v) by promoting mediation as the primary problem-solving mechanism; and

- (vi) by reducing the need for judicial intervention; and

- (b) to promote observance in New Zealand of the principles underlying International Labour Organisation Convention 87 on Freedom of Association, and Convention 98 on the Right to Organise and Bargain Collectively.

This is a different Act from the ECA 1991 with its emphasis on ‘productive employment relationships’, ‘addressing the inherent inequality of bargaining power’, making good faith an overarching duty, moving the terminology from contracts to agreements, and seeing collectivism as part of the solution (rather than as the problem) of moving towards productive and fair employment relationships. The support of collectivism (collective employment agreements – CEAs) came in several forms, such as:

- Union ‘ownership’ of collective agreements; thereby disallowing ‘collective contracting’

- 30-day rule: new employees join existing CEA

- Unions could initiate bargaining before employers

- Multi-employer CEAs no longer have strike restrictions

- Union registration was re-introduced

However, there was no duty to conclude collective bargaining negotiations, awards were not reinstated, and the conclusion of multi-employer agreements appeared convoluted and difficult in the face of employer resistance. Importantly, the individualistic nature of the ECA 1991 also appeared in several parts of the ERA 2000, and it appeared that the government introduced something like the ‘two-handed approach’ of the Labour Relations Act 1987 (see Chapter 3). With ‘collective contracting’ no longer being an option for employers, it was probably a surprise that the expected rise in CEAs in the private sector did not happen. Instead, many of the collective contracts became individual employment agreements (IEAs) to fit with the new regulations.

A comprehensive 2002–2003 analysis of trends under the ERA 2000 found that in most workplaces it was ‘business as usual’ (Waldegrave et al., 2003; Waldegrave, 2004a & 2004b). There had not been a shift towards collectivism and the vast majority of employees, particularly in small private sector workplaces, were on IEAs. It also appeared that most employers and employees were quite happy with their workplace employment arrangements, though this was not the case for a significant minority of employees where low pay, unsatisfactory working conditions and career prospects fell short of ‘productive employment relationships’. Surveys in the late 1990s had found a similar distinction between employee groups (Waldegrave et al., 2003, p. 21) and thus, the aspirations of moving towards a different form of employment relations were unfulfilled.

The Labour Coalition Government reacted by suggesting further legislation which the political opposition and employers greeted, like in 2000, with a strong campaign of criticism and hostility. However, the government went ahead with its changes to support good faith, the promotion of collective bargaining and facilitating union activities and membership (for an overview, see Rasmussen, 2009, pp. 159-163). There were also changes to statutory minimum wages, parental leave and the Holidays Act that ensconced youth statutory minimum wages, paid parental leave (introduced in 2002) and a fourth week of annual leave.

While the legislative changes continued the strong feature of policy-induced changes, especially in terms of statutory minima, there appeared to be very limited impact on bargaining processes and outcomes. The impact of good faith on workplace relationships was unclear and collective bargaining and union membership were stagnant. In fact, there was hardly any progress in moving outside the traditional strongholds of unions in the public sector and larger private sector businesses. This prompted a discussion of why the expected upswing in private sector collective bargaining had not happened (see below).

Besides the strong rise in individual statutory minima – for example, a rise in the adult statutory minimum wage of 59% during 2000–2008 – there was a more buoyant labour market and skill shortages were a major media and policy topic during 2003–2008. There were clear benefits for a large part of the workforce with more job opportunities, higher pay, better working conditions and increased emphasis on employee-friendly flexibility. Skill shortages also prompted a stronger tripartite focus on vocational training and education (see Chapter 6). Still, there was insufficient movement amongst low-paid employee groups and disappointing productivity growth highlighted the concerns about the elusive goal of ‘productive employment relationships’ (see Chapter 6).

Phase 2: the Key/English Governments, 2008–2017

The fifth National Government was elected in October 2008. The initial years of the National-led Governments were strongly influenced by changing economic circumstances where the Global Financial Crisis shifted labour market settings considerably from a tight labour market with skills shortages to an unpredictable labour market with several OECD countries recording sharp rises in unemployment (Cazes et al., 2013). The crisis feeling was further escalated by the Christchurch earthquakes in 2010–11 which devastated New Zealand’s third largest city. While unemployment was contained below 7% in the 2008–2012 period, there were clearly significant economic, labour market and social pressures, including a considerable deterioration of the country’s fiscal position as the government borrowed heavily.

Prior to the 2008 election campaign, the new leader of the National Party, John Key, had shifted the National Party’s position from abolishing the ERA 2000 to promising specific changes in particular areas. These changes included: a ‘probationary’ period where new employees could agree to forego their personal grievance rights (subsequently termed the ‘90-day trial period’), removing the monopoly rights of unions of collective agreements, revisiting the Holidays Act, and removing Accident Compensation Corporation’s (ACC) monopoly over workplace insurance costs (Rasmussen & Anderson, 2010).

Interestingly, it appeared that employment relations were not one of the main platform policies for the incoming National-led Government in 2008. It presented its plans as just a tweaking of the legislative frameworks rather than a root-and-branch reform (Haworth, 2011). Although the government quickly introduced the 90-day trial period for small businesses, it was through its subsequent terms in parliament that it made several changes to the ERA and other pieces of employment relations legislations (see Table 4.2).

The changes to personal grievance rights of new employees were clearly a major political point of disagreement and generated both considerable support and opposition. The changes were promoted as ‘building flexibility and creating jobs’ as well as ‘bringing balance to labour market rules’ (National Government Employment Relations Policy, 2011). There was strong employer support for the 90-day trial periods and even employers who did not apply trial periods in their own workplaces, were supportive of ‘more flexibility’ (Foster et al., 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2016). On the other hand, unions were strongly opposed to the undermining of individual personal grievance rights and they campaigned vigorously to have them overturned. This was also the Labour Party’s policy in the 2017 General Election but the government decided, in 2018, that smaller businesses (less than 20 employees) could continue to negotiate 90-day trial periods (see below). Thus, this returned the employee personal grievance rights to the situation before the 2010 changes (see Table 2).

There was considerable debate over the effectiveness of the 90-day trial periods. Most the research by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) was focused on employers and their approaches. Subsequently, MBIE developed a very comprehensive survey of employers – the National Employer Survey – which so far has recorded annually the opinions and work practices of employers since 2015 (MBIE, 2019). The MBIE surveys, together with several surveys conducted by employer associations, clearly found that employers were in favour of the 90-day trial periods. These sentiments were also mirrored in independent surveys (see Foster et al., 2013).

| Legislation | Legislative purpose and details |

| ER Amendment Act 2008 | Introduce 90-day probation/trial period for small businesses (1 to 19 employees) |

| ER Amendment Act 2010 | Extend 90-day trial period to all organisations, reduced union access rights, reinstatement is no longer primary remedy in dismissal cases, change dismissal test from what a reasonable employer ‘would’ instead of ‘could’ have done |

| Holidays Amendment Act 2010 | Employers can require proof of sickness from the first day, allow employees to trade for cash their fourth week of annual leave |

| ER (Film Production Work) Amendment Act 2010 | ‘Hobbit’ legislation prescribes ‘contracting’ for film production workers |

| ER (Secret Ballots for Strikes) Amendment Act 2012 | Before taking strike action, unions need to conduct secret ballots of members |

| ER Amendment Bill 2013 (implemented after the 2014 General Election) |

The Accident Compensation Act underwent two amendments in 2008 and 2010. The amendments were primarily concerned with reducing the number of claims and associated costs.

Source: Foster & Rasmussen, 2017, p.102

While there was no doubt that employers generally agreed to the 90-day trial period and that unions were strongly opposed to it, there was less clarity about the impact on employees and associated employment effects. The government argued that many people continued their employment past the 90 days and that a ‘hassle-free’ trial period created many additional jobs. However, 2016 research by economic research institute, Motu, found very limited or no employment effects: ‘We find no evidence that the ability to use trial periods increases firms’ overall hiring; /… / We also find no evidence that the policy increased the probability that a new hire by a firm was a disadvantaged jobseeker…’ (Chappell & Sin, 2016, pp. i-ii). Thus, the jury is still out regarding positive or negative effects, though it is obvious that this is an intervention that divides the main political parties (see below).

The National Party had promised in the 2008 election that it would revisit the Holidays Act. This resulted in the specific changes which allow employees to ‘trade in’ their fourth week of holiday for cash. However, a major overhaul of the Holidays Act did not happen and its application could often be problematic for employers and generated a fair amount of disagreement between employers and employees. There have also been several cases where employers have deliberately withheld holiday payments (see below). A major overhaul of the Holidays Act is still on the agenda and the 2017 Labour-led Government tasked a working group to come up with suitable recommendations which prompted subsequently a legislative amendment scheduled for 2022.

Interestingly, the ability to ‘trade in’ a week of annual leave had already been suggested by the National-led Government in 1998 (Rasmussen & Anderson, 2010, p. 220) but it was never implemented. This would have been a more significant shift in practice as annual leave at that time was still three weeks and was not increased until 2007. Likewise, the election promise of removing ACC’s monopoly over workplace insurance costs was also a resurrection of a policy of the 1990s where the National-led Government implemented such a change in 1998, which was subsequently overturned by the Labour-led Government in 2001 (see Chapter 5). Despite some government and business criticism of ACC over its levies and bureaucratic structure during the 2008–2017 period, there was never any legislative appetite to abolish ACC’s workplace insurance role as it fulfilled several functions, including compensation, rehabilitation and prevention.

Although there was a strong focus on adjusting individual employee rights during 2008–2017, there was also a number of changes to the role of unions and collective bargaining (see Table 4.2). These changes happened in several stages. In 2010, the unions’ right of access to workplaces was curtailed with employer consent necessary before unions could enter workplaces and discuss union matters with employees. In 2012, unions’ ability to take strike action was constrained as they had to conduct secret ballots of their members before taking action. In 2014, there were changes to bargaining processes of multi-employer agreements which allowed employers to stall and avoid negotiations over multi-employer agreements. There were also changes to unions’ ability to take strike action with tougher notice requirements and employer ability to deduct pay over partial strikes. These changes – and other minor regulatory changes – made it more difficult for unions to conduct collective bargaining and it is difficult to see how the changes aligned with the ERA’s Objectives and their emphasis on promoting collective bargaining.

A particular intervention against unionism and collective bargaining was the so-called ‘Hobbit’ law changes in the film production industry (see the detailed discussion in New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 36(3)). As highlighted in the detailed discussion below, it was triggered by a collective bargaining dispute, but its prior history related to legal court cases over the employment status – contractor or employee – of a worker at the film company, Three Foot Under, associated with filmmaker, Peter Jackson. A government legislative intervention designated all film production workers as contractors where both the content and processes surrounding the intervention made this a controversial public policy change.

In conclusion, the changes to employment relations that occurred under the National-led Governments were aimed at enhancing labour market flexibility and employers’ ease of conducting business. The changes were initially driven by the fear of a strong rise in unemployment and business failures as the Global Financial Crisis put major pressure on labour markets in most OECD countries. It also aimed, as discussed in Chapter 6, at improving workplace productivity and thus, according to Department of Labour, ‘…the changes are aimed at creating a more flexible and responsive labour market, which in turn is expected to contribute indirectly to improved productivity in a number of sectors’ (Department of Labour, 2010, p. 5).

However, as the pressure from the Global Financial Crisis eased, a less clear-cut public policy pattern developed during 2013-2017. On one hand, the search for ‘a more flexible and responsive labour market’ and the promotion of more individualised employment relations continued as reflected in the Employment Relations Amendment Act 2014. On the other hand, the growing concerns about employment conditions and their corresponding social impact resulted in the National-led Government implementing further employment regulation and highlighting the importance of employment standards (see Table 4.2).

Phase 3: The initial years of the Ardern Governments, 2017-onwards

The 2017 General Election was a close fought battle and included two new party leaders, with Bill English becoming Prime Minister and leader of the National Party when Prime Minister John Key resigned in December 2016, and Jacinta Ardern becoming leader of the Labour Party in August 2017. As a coalition government was the likely election outcome, there was also an interest in the minor parties’ election manifestos (Skilling & Molineaux, 2017). After the Labour Party and New Zealand First reached a coalition agreement, a coalition government with Labour and New Zealand First, and with the support of the Green Party, was formed in October 2017.

It was obvious from their election manifestos that the Labour Party-New Zealand First coalition agreement and subsequent policy announcements would herald a significant change to existing employment relations (Coalition Agreement, 2017; Foster & Rasmussen, 2017). This included a reversal of changes implemented in 2008–2017 and new initiatives to enhance collectivism, employee protection and promote fairness and equality in the labour market. These significant changes included: large annual increases in the statutory minimum wage towards the goal of $20 by early 2021, an increase in paid parental leave from 22 to 26 weeks from July 2020, and the promotion of a ‘living wage’ for public sector employees. An interesting development was the Equal Pay Amendment Act which came into force in November 2020. It has been suggested that this Act could cause an upheaval of pay structures, given the already considerable impact of the pay equity changes in the aged-care sector.

As can be seen from Table 4.3, the Employment Relations Amendment Act 2018 reversed several of the 2008–2017 interventions. It is surprising that the Labour Coalition Government did not abolish totally the 90-day trial periods, but these can still be pursued by small businesses with less than 20 employees. This reversal brings back the 2010 situation, instead of the pre-December 2008 situation where all employees had a personal grievance right. While there were some initiatives to promote union membership, it is still too early to say whether it will overcome the stagnation in union density.

Although there have been several changes post-2017, there are still many more changes which could prove significant as the 2017–2020 government launched several working groups, legislative reviews and expert discussions. This has included working groups on Fair Pay Agreements, the so-called ‘Hobbit’ legislation about contractors in the film production industry, the link between social welfare and employment, and a review of the Holidays Act. A major restructuring of vocational education and training was announced in 2019 and is under implementation in 2020–2021 (see Chapter 6).

| Changes in effect from 12 December 2018 | Changes in effect from 6 May 2019 |

| Union representatives can now enter workplaces without consent, provided the employees are covered under, or bargaining towards, a collective agreement | The right to set the number and duration of rest and meal breaks will be restored |

| Pay deductions can no longer be made for partial strikes | 90-day trial periods will be restricted to businesses with less than 20 employees |

| Businesses must now enter into bargaining for multi-employer collective agreements, if asked to join by a union | Employees in specified ‘vulnerable industries’ will be able to transfer on their current terms and conditions in their employment agreement if their work is restructured, regardless of the size of their employer |

| Employees will have extended protections against discrimination on the basis of their union membership status | The duty to conclude bargaining will be restored for single-employer collective bargaining |

| If requested by the employee, reinstatement will be the first course of action considered by the Employment Relations Authority | For the first 30 days of their employment, new employees must be employed under terms consistent with the collective agreement |

| Earlier initiation timeframes have been restored for unions in collective bargaining | Pay rates will need to be included in collective agreements |

| New categories of employees may apply to receive the protections afforded to ‘vulnerable employees’ | Employers will need to provide new employees with an approved active choice form within the first 10 days of employment and return forms to the applicable union |

| Employers will need to allow for reasonable paid time for union delegates to undertake their union activities | |

| Employees will need to pass on information about the role and function of unions to prospective employees |

Source: Skilling, 2019, p. 64

As various changes are still unfolding or being discussed, it is difficult to make a precise evaluation of the employment relations policies of both the 2017–2020 coalition government and the current Labour Government. With the 2020 General Election resulting in a majority Labour Government, it appears likely that many policy recommendations could be phased in during 2021–2023.

Overall, the changes are more in line with the ERA’s object clause and policy intentions (compared to the 2008–2017 changes), though whether they will deliver on establishing more ‘productive employment relationships’ and promoting collectivism are still unclear. Furthermore, the economic, social and labour market upheavals resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic make it even more difficult to predict public policy changes in employment relations (see Chapter 6). Several major industries – for example, tourism, hospitality and retail – have recorded significant employment losses and they will take considerable time to overcome the current downturn as a result of the Covid-19 restrictions. While a major effort in vocational training and education has been signalled, it is unclear how the government will prioritise new regulatory interventions, including support of low-paid employees.

Unions, bargaining outcomes and labour market changes

As mentioned, the ERA supported explicitly collectivism and positioned it as part of the solution – rather than a barrier – in moving towards ‘productive employment relationships’. Despite several positive interventions in the ERA to support collectivism, it is clear from Table 4.4 below that the legislative intentions have not translated into union membership growth. In fact, the union density figures – as a percentage of employees – hide a decline in private sector unionism under the ERA: union density is still high in the public sector with around 60% being union members while union density has hovered around or below 10% in the private sector in recent years. Thus, there are many private sector workplaces where union activity is very limited or non-existent.

| Month | Year | Number of unions | Membership | Density (%) |

| September | 1989 | 112 | 648 825 | 44.7 |

| May | 1991 | 80 | 603 118 | 41.5 |

| December | 1991 | 66 | 514 325 | 35.4 |

| December | 1995 | 82 | 362 200 | 21.7 |

| December | 1999 | 82 | 302 405 | 17.0 |

| December | 2000 | 134 | 318 519 | 21.6 |

| December | 2004 | 170 | 354 058 | 21.1 |

| December | 2008 | 147 | 384 777 | 21.4 |

| December | 2011 | 134 | 372 891 | 20.5 |

| December | 2014 | 125 | 361 491 | 18.5 |

| March | 2017 | 124 | 355 511 | 17.2 |

Sources: Ryall & Blumenfeld, 2015; Companies Office, 2018

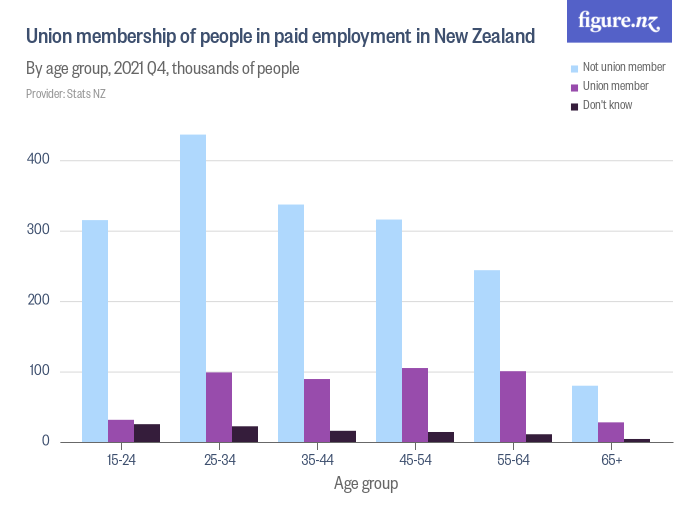

Since the start of the ERA, there has been a rise in the number of new and larger unions, often as a result of amalgamations, for example, E tū. One of the reasons for the creation of new unions is the ‘ownership’ of collective agreements by certain unions (Barry & May, 2004; Murrie, 2006). Recruiting new, younger members to replace retired workers in relatively stable employment is also problematic, as shown in the graphs below. Some younger workers can be changing jobs often, being precariously employed and holding down multiple jobs, thus making union recruitment difficult. Additionally, the prevalence of small businesses is clearly a problem for effective union organising and so are sectors with high staff turnover with union recruitment of new members being a constant, ongoing task. Still, it has probably surprised some commentators that unions have had so little success under a positive legislative framework.

Figure 4.2 Union membership

Why have unions not been more successful in growing membership and lifting union density under the ERA? There are numerous factors and explanations in play and many of them have been mentioned in the debate (for an overview, see Rasmussen, 2009, pp. 129-133):

- Many private sector workplaces are not conducive to effective union organising because of factors such as their size and their high staff turnover. This is often linked to the ‘presentation gap’ concept where employees may want to become union members but they have little or no option as union activity does not cover their workplace.

- The so-called ‘passing on’ of union negotiated benefits featured strongly in the debate of the early 2000s and was sought to be addressed by the ER Amendment Act 2004. However, many employers like to have similar pay and conditions across their workforce, and this makes ‘passing on’ a normal practice.

- ‘Free-loading’ or ‘free-riding’ have been a traditional argument (Olson, 1980; Crouch, 1982) where employees decide against union membership as they may obtain the same or nearly similar pay and conditions as union members (Waldegrave et al., 2003, pp.76-77). The existence of ‘passing on’ will encourage such an employee decision.

- The growth in individual employment rights and minima and a buoyant labour market have also been mentioned as a problem (Rasmussen et al., 2006). With a sharp rise in statutory minima and employers facing skill and staff shortages, many employees have received improvements outside of collective agreements (aligned with points 1 and 3 mentioned above).

- Employee apathy or disinterest has also been an argument since many employees have expressed satisfaction with their employment relationships or they would prefer to deal with any dissatisfaction themselves (Haynes et al., 2006).

- Employers’ negative attitudes towards collective bargaining or reluctance to enter into collective bargaining have been seen as a major stumbling block, whether or not a particular employer has actively resisted collective bargaining taking place.

Thus, unions have had limited success in extending collective bargaining coverage in the post-2000 period (Blumenfeld & Donnelly, 2017). Public sector collective bargaining coverage has been solid and has increased from the ECA 1991 period (in fact, it has increased since 1995). The large, homogenous public sector workforce – for example, in education, health and core public sector – provides an easier workforce to organise for unions. There is also often an overlap between collective bargaining and occupational identity; something evident in recent public sector disputes. However, the lower number of employees in the public sector – around 6 times smaller than the private sector workforce – means that the overall collective bargaining coverage is dragged down by the drop in private sector collective bargaining.

The link between collective bargaining coverage and union membership has been strong under the ERA 2000 with ‘collective contracting’ not being an option. It is necessary, therefore, for unions to find a way of both enhancing private sector collective bargaining and increase private sector union density. This has been addressed by union leaders previously (Harré, 2010; Kelly, 2010) and there are some union expectations that recent ERA amendments, Fair Pay Agreements and other supports of collective bargaining may be able to enhance the unions’ membership initiatives. As the final form of the current government’s employment relations policies has yet to be established, and as many of the structural and embedded barriers (as discussed above) are still in evidence, a turnaround in union density and membership and collective bargaining coverage is highly unpredictable.

Employment law under the Employment Relations Act

Under the ERA 2000, there have been several high-profile court decisions (though less pronounced compared to the 1990s). There have been some links between legislative interventions and court decisions in a couple of key areas, such as employment status (the Bryson case), pay equity (the Bartlett case), employment standards, and collective bargaining. Court decisions have provided clarification on a number of issues, such as availability to work overtime, payment for rest breaks and meetings, redeployment in organisational restructuring (Kiely, 2018; 2019). However, the fundamental political disagreements surrounding the ERA 2000 – see the 3 phases described above – have also left a number of issues to be re-litigated, unresolved or bypassed in silence. Amongst these issues are the Holidays Act, employment status (particularly involving rights and protection of contractors), pay equity and employment standards.

The employment status of workers – whether they are employees or contractors – has been tested in several court cases, with the decisions in the so-called Bryson case playing a major role. The case between Mr Bryson, working on the Lord of the Rings film series, and Peter Jackson’s production company, Three Foot Six Limited, was tested at the Employment Court, the Court of Appeal and finally at the Supreme Court (see Nuttall & Reid, 2005; Rasmussen, 2009, pp. 378-9). The final outcome was that Mr Bryson was considered an employee and he was covered, therefore, by statutory employee rights. The case sends a strong message to employers that they should consider the actual relationship with a worker; just labelling a worker a contractor was insufficient. For workers in the film production industry, this changed with ‘Hobbit’ legislation in 2010 where workers in that industry were deemed to be contractors (see New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 36(3)). This controversial legislation is still under consideration as is the legal decision-making on workers’ employment status, with new legislative initiatives expected in 2022.

As shown above, unions have not gained traction under the ERA 2000. It can be argued that a number of court decisions have hampered unions’ ability to bargain for multi-employer agreements (MECAs), to resist employers’ attempt to bypass unions in negotiations, and to break bargaining deadlocks. Employers have been successful in arguing that they should not be forced into a MECA against their wishes. This has proven, besides the cumbersome rules surrounding MECA negotiations, to be a nearly impossible hurdle for the unions to overcome. There have been several court cases dealing with employers attempting to bypass unions during bargaining, either through proposing individual employment agreements or communicating directly with employees. While unions have succeeded in curtailing some employer behaviours, it has proved difficult to avoid direct communication and the lure of individual employment agreements. Finally, the introduction of facilitation as a new approach in the ER Amendment Act 2004 has also had less than expected impact (see Scott, 2019). The outcome from early cases in front of the Employment Relations Authority signalled a very high threshold before the Authority would apply facilitation: lengthy unresolved negotiations and even industrial disputes were not seen as being sufficient. Therefore, there have been very few cases accepted for facilitation since this new dispute resolution method was introduced in 2004.

While unions have been faced with some adverse court decisions, they have also had important wins. In the famous Bartlett or Terranova case, the Service and Food Workers Union pursued the pay equity claim of Kristine Bartlett which was finally upheld when the Court of Appeal supported the previous Employment Court decision. As this decision would have opened for many other court cases, the government decided – following recommendations from a tripartite working group – to underwrite a substantial pay rise for over 50,000 care workers by implementing a $2 billion package in July 2017.

Another key win, the Employment Standards Act 2016, was mainly driven by concerns raised by union campaigns (targeting the unfairness of ‘zero hours’ agreements) though there were also a number of court cases which highlighted unsatisfactory employment standards. In particular, the Employment Institutions have started to impose severe fines on employers who exploit vulnerable workers, and there are now more labour inspectors and a more proactive approach to enforce employment standards.

Beyond legal precedent, the Employment Institutions have also been very active and dealt with a large number of cases. The Mediation Service is dealing with over 15,000 disputes a year: in 2018, over 8,000 cases were heard by the Mediation Service, and it also signed off on another 8,000 plus settlements concluded directly by the parties themselves (Franks, 2018). The Employment Relations Authority and the Employment Court have also been kept busy, and their cases are often setting or adjusting legal precedent. Still, there are concerns that there are barriers to conflict resolution which prevent some workers and employers to pursue their employment relationship problems. These barriers are often associated with the ERA’s expectation that employees have the ability and the inclination to pursue employment relations problems either at the workplace or at the Employment Institutions. This can be an unrealistic expectation since there can be many reasons why employees may not pursue their rights. Instead, many of these employees can opt to keep silent or just leave the workplace.

Conclusion

The ERA 2000 was envisaged as a major break from previous employment legislation, setting the scene for more relational, trust-based employment relationships. As the Act has been in force for two decades, its longevity means that many practitioners have just a dim view of previous employment relations approaches. However, the ECA 1991 is still casting its long shadow over employment relations practices and some of the expectations of more collective bargaining, higher union membership and ‘productive employment relationships’ have not been fulfilled. Importantly, the controversial status of employment relations legislation is still lingering on and has come to the fore when general elections and major changes occur.

While the main original parts of the ERA 2000 are still intact, there have been many amendments in the post-2000 period. The three phases presented in this chapter show a distinct difference in the various governments’ support of the ERA’s objectives. Although the Labour-led Governments in 2000–2008 and post-2017 have been active in supporting the objectives of collectivism and improved employee protection, there were more mixed signals under the 2008–2017 National-led Governments. While collective bargaining has stagnated, there has been a strengthening of individual employment rights, and these rights, including the personal grievance right, have now become embedded in New Zealand employment relations.

The political struggles over the particular changes to the ERA 2000 as well as the realities of the changing nature of work will probably be debated for a while and this will make employment relations less consensual and stable. In this environment, it is unclear how well the wider concerns of low productivity growth, insufficient training and skill development, a fragmented labour market and an associated low wage economy can be addressed. There are also conflicts over the appropriate level and forms of labour market flexibility where employer demands for further increases in employer discretion is confronted by worker demands of improved protections and flexible working arrangements. Finally, these concerns and conflicts have yet to be influenced by the expected major upheaval associated with the ‘future of work’ and radical shifts in work and employment patterns, and this could prompt a range of new challenges for employment relations regulations (see Chapter 6).

References

Barry, M. & May, R. (2004). New employee representation: Legal development and New Zealand unions. Employee Relations, 26(2), 203-223.

Blumenfeld, S. & Donnelly, N. 2017. Collective Bargaining Across Four Decades: Lessons from CLEW’s Collective Agreement Database. In Anderson, G. et al. (eds.), Transforming Workplace Relations in New Zealand 1976-2016 (pp. 107-128). Victoria University Press.

Bray, M., Waring, P., Cooper, R. & Macneil, J. (2018). Employment Relations. Theory and Practice. 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill Education.

Burton, B. (2004). The Employment Relations Act according to Business New Zealand. In Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). Employment relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act (pp. 134-144). Auckland University Press.

Burton, B. (2010). Employment relations 2000–2008: an employer view. In Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). Employment relationships: workers, unions and employers in New Zealand (pp. 94-115). Auckland University Press.

Campbell, I. (2018). Zero-hour work arrangements in New Zealand: Union action, public controversy and two regulatory initiatives. In O’Sullivan, M., Lavelle, J., McMahon, J., Ryan, L., Murphy, C., Turner, T. & Gunnigle, P. (Eds.). Zero Hours and On-call Work in Anglo-Saxon Countries (pp. 91-110). Springer.

Cazes, S., Verick, S. & Al Hussami, F. (2013). Why did unemployment respond so differently to the global financial crisis across countries? IZA Journal of Labour Policy, 2(10), 1-18.

Chappell, N. & Sin, I. (2016). The Effect of Trial Periods in Employment on Firm Hiring Behaviour. New Zealand Treasury Working Paper 16/03, June 2016, NZ Treasury.

Coalition Agreement. (2017). Coalition Agreement New Zealand Labour Party and New Zealand First. October 2917, NZ Parliament.

Companies Office. (2018). Union membership return report 2018. Downloaded from: www.companiesoffice.govt.nz on 17 November 2019.

Crouch, C. (1982). Trade Unions: the Logic of Collective Action. Fontana.

Department of Labour. (2010). Annual Report 2010. Department of Labour.

Foster, B., Murrie, J. & Laird, I. (2009). It Takes Two to Tango: Evidence of a Decline in Institutional Industrial Relations in New Zealand. Employee Relations, 31(5), 503-514.

Foster, B., Rasmussen, E., Laird, I., & Murrie, J. (2011). Supportive legislation, unsupportive employers and collective bargaining in New Zealand. Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 66(2), 192-212.

Foster, B., Rasmussen, E. & Coetzee, D. (2013). Ideology versus reality: New Zealand employer attitudes to legislative change of employment relations. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 37(3), 50-64.

Foster, B. & Rasmussen, E. (2017). The major parties: National’s and Labour’s employment relations policies. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2), 95-109.

Franks, P. (2018). Barriers to participation: a mediator’s perspective. Paper at AUT Symposium, see: www.workresearch.aut.ac.nz .

Geare, A., Edgar, F. & McAndrew, I. (2006). Employment Relations: Ideology and HRM Practice. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(7), 1190-1208.

Geare, A., Edgar, F. & McAndrew, I. (2009). Workplace Values and Beliefs: An Empirical Study of Ideology, High Commitment and Unionisation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20(5), 1146–1171.

Harré, L. (2010). Collective bargaining – right or privilege? In Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). Employment relationships: workers, unions and employers in New Zealand (pp. 24-39). Auckland University Press.

Haworth, N. (2011). A Commentary on Politics and Employment Relations in New Zealand: 2008–2011. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 36(2), 23-32.

Haynes, P., Boxall, P. & Macky, K. (2006). Union reach, the ‘representation gap’ and the prospects for unionism in New Zealand. Journal of Industrial Relations, 48(2), 193-216.

Kelly, H. (2010). Challenges and opportunities in New Zealand employment relations: a CTU perspective. In Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). Employment relationships: workers, unions and employers in New Zealand (pp. 133-148). Auckland University Press.

MBIE. (2019). National Survey of Employers 2017/18. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

McAndrew, I., Edgar, F. & Jarrard, M. (2018). Human Resource Management and Employment Relations Paradigms in Australia and New Zealand. In Parker, J. & Baird, M. (Eds.). The Big Issues in Employment (pp. 1-19). Wolters Kluwer.

Murrie, J. (2006). Not a typical union but a union all the same: New unions under the Employment Relations Act 2000. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 31(2), 31-45.

Nuttall, P. & Reid, F. (2005). Three Foot Six Limited v Bryson CA 246/03 12 November 2004 – legal comment. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 30(1), 87-92.

Olson, M. (1980). The Logic of Collective Action. Harvard University Press.

Rasmussen, E. (2009). Employment Relations in New Zealand. Pearson.

Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). (2004). Employment relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act. Auckland University Press.

Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). (2010). Employment relationships: workers, unions and employers in New Zealand. Auckland University Press.

Rasmussen, E. & Anderson, D. (2010). Between unfinished business and an uncertain future. In Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). Employment Relationships. Workers, Unions and Employers in New Zealand (pp. 208-223). Auckland University Press.

Rasmussen, E., Hunt, V. & Lamm, F. (2006). Between individualism and social democracy. Labour & Industry, 17(1), 19-40.

Rasmussen, E., Fletcher, M., & Hannam, B. (2014). The major parties: National’s and Labour’s employment relations policies. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 39(1), 21-32.

Rasmussen, E., Foster, B. & Farr, D. (2016). The battle over employer-determined flexibility: attitudes amongst New Zealand employers. Employee Relations, 38(6), 1-23.

Ryall & Blumenfeld, S. (2015). Union and Union Membership in New Zealand – Report on 2015 Survey. Victoria University.

Scott, J. (2019). Mediation and Facilitation of Collective Employment Disputes in New Zealand from a Historical and Comparative Perspective. MPhil Thesis, Auckland University of Technology.

Skilling, P. (2019). Another swing of the pendulum: rhetoric and argument around the Employment Relations Amendment Act (2018). New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 44(1), 110-128.

Skilling, P. & Molineaux, J. (2017). New Zealand’s minor parties and ER policy after 2017. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 42(2), 110-128.

Waldegrave, T. (2004a). Employment relationship management under the Employment Relations Act. In Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). Employment relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act (pp. 119-133). Auckland University Press.

Waldegrave, T. (2004b). Employee experience of employment relationships under the Employment Relations Act. In Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). Employment relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act (pp. 145-158). Auckland University Press.

Waldegrave, T., Anderson, D. & Wong, K. (2003). Evaluation of the short term impacts of the Employment Relations 2000. Department of Labour.

Wilson, M. (2004). The Employment Relations Act: a framework for a fairer way. In Rasmussen, E. (Ed.). Employment relationships: New Zealand’s Employment Relations Act (pp. 9-20). Auckland University Press.

License

Employment Relations in the new millennium Copyright © 2022 by Erling Rasmussen; Felicity Lamm; and Julienne Molineaux is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.